29 October 2025

|

A recent report from the Environmental Investigation Agency highlights how refrigeration is driving climate change and how retailers can lead the way. Fionnuala Walravens, Senior Climate Campaigner, EIA UK, maps out the cooling pathway.

The cooling industry is at the heart of one of the greatest climate challenges of our time. From hypermarkets in Europe to corner stores across the globe, refrigeration keeps food safe and supply chains moving. But it comes with a heavy environmental cost. According to Cooling the Climate Crisis*, a recent analysis by the Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA), as much as 70% of a supermarket’s non-supply chain (Scope 1 and 2) emissions can be traced to cooling.

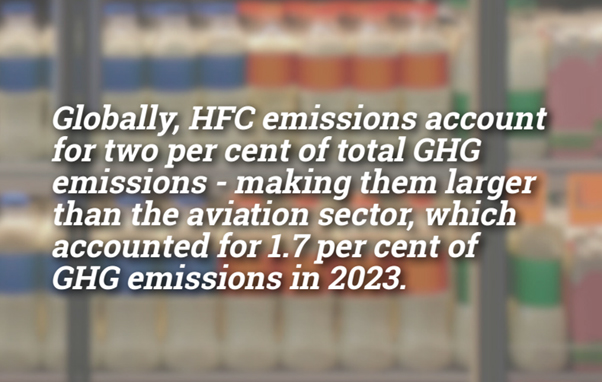

These emissions stem from two major sources: energy use and refrigerant leakage. Both have a significant climate impact, but refrigerants tell the sharper story. Hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) – the most widely used refrigerants in commercial refrigeration – are thousands of times more potent than CO₂. Combined with high leakage rates, emissions from commercial refrigeration often account of a larger share of the energy used by these systems.

The good news? The industry already has proven, cost-effective alternatives. And the direction of travel is clear: natural refrigerants, energy efficiency, and transparent climate strategies are not optional extras. They are fast becoming the benchmark for competitiveness, compliance, and credibility.

Refrigeration’s climate footprint

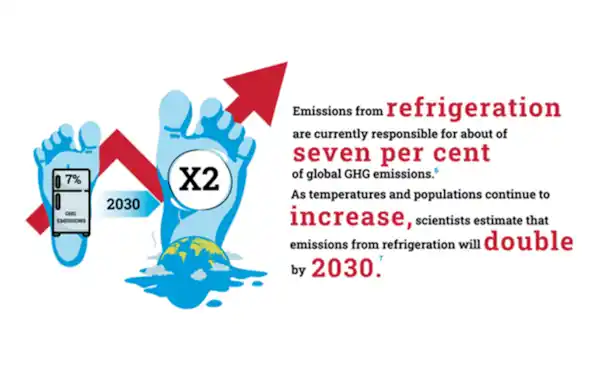

Globally, refrigeration is responsible for around 7% of greenhouse gas emissions, whilst HFC emissions are more significant than those from the aviation sector. Although international agreements such as the Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol aim to phase down HFCs, current trajectories remain insufficient to limit warming to 1.5°C.

Fortunately, accelerated action from Europe is driving change. The EU’s updated F-Gas Regulation is the most ambitious in the world, set to prevent 500 million tonnes of CO₂-equivalent emissions by 2050. This has tightened HFC supply, driven up prices, and sharpened the financial risks of clinging to old HFC based systems. The situation is not uniform worldwide, but the trend is universal; retailers and their refrigeration partners must prepare for an accelerated transition and rising HFC costs.

Despite industry challenges, sustainable cooling is scaling rapidly. Systems based on natural refrigerants – CO₂, hydrocarbons, and ammonia – are now mainstream across Europe. With CO₂ transcritical systems installed in about 30% of EU supermarkets.

How the big retailers compare

EIA’s report analyses data from five European retail giants, highlighting both progress and gaps:

- Ahold Delhaize emitted around 2.16 million tonnes CO₂e from cooling in 2023. Its commitment to adopt natural refrigerants by 2040 lags EU timelines, and progress in the US is minimal, with an earlier report by EIA on US supermarkets, noting that less than 1% of its US stores running on refrigerants with a GWP of less than 10.

- Carrefour has a €650 million plan to convert 406 hypermarkets and has trained technicians on natural refrigerant systems. Yet, only 19% of its stores are currently HFC-free, and smaller stores are not fully accounted for.

- Jerónimo Martins stands out with 57% of its stores running on low-GWP systems, and nearly complete conversion in Colombia. The retailer also leads on Scope 3 (supply chain) emissions, reporting that 70 percent of its refrigerated shipping uses natural refrigerants. Its global HFC phase-out target is set for 2035.

- Metro AG has allocated €1.1 billion to eliminate HFCs, pledging a 90% phase-out by 2030 and full global phase-out by 2040. Half of its stores already run on natural refrigerants, including those outside Europe where regulation is weaker.

- Tesco has committed to a 2035 HFC phase-out, with a third of its stores already converted. Notably, it is the only retailer in the report to use natural refrigerants in refrigerated road transport. However, its public disclosures lack detail and transparency compared to peers.

The financial case for F-Gas-free refrigeration

Beyond compliance, natural refrigerants make strong financial sense. While upfront costs can be higher, systems typically pay back in four to ten years, well within their 15-year operating life. Carrefour reports energy savings of 7-25% compared to older HFC systems, adding doors to cabinets can lift reductions to 45%.

At the same time, the rising cost of HFCs is already eroding the bottom line. Some refrigerants have seen price hikes of up to 800% in Europe. On top of that, compliance penalties are an increasingly real risk. Carrefour, for example, has calculated that non-compliance with EU F-Gas rules could amount to €100,000 per hypermarket—a potential €40.6 million liability across its European estate. Taken together, these figures make the business case for transitioning to natural refrigerants as clear as the environmental one.

EIA’s Net Zero supermarket cooling pathway

In short, delaying the transition is not only environmentally damaging but financially unsustainable. Drawing on our extensive experience in monitoring and reporting on this sector during the past two decades as well as best practices of the featured retailers, EIA has developed a Net Zero Supermarket Cooling Pathway summarised here:

1. Disclosing Data

Retailers should publish clear information on cooling-related emissions, including the extent of HFC use, roadmaps for conversion, associated costs and risks, and progress toward natural refrigerant adoption. At least 6% of capital expenditure should be dedicated to sustainable cooling, supported by supplier engagement.

2. Cutting Refrigerant Emissions

Companies must commit to natural refrigerant-only cooling in Europe by 2030 and globally by 2040. Immediate steps include reducing leakage, recovering refrigerants from old systems, and ensuring all new stores and distribution centres are HFC-free. Trials in transport refrigeration should prepare the ground for full adoption.

3. Reducing Energy Used for Cooling

By 2030 retailers should cooling-related energy emissions target by 55%. This means retrofitting fridge doors, expanding renewable energy generation, and considering heat recovery. Other actions include optimising freezer settings, adopting passive cooling, switching to LED lighting, and supporting the development of more efficient equipment.

4. Engaging with Supply Chains

Supermarkets must extend action beyond their own operations by working with suppliers to cut cooling-related emissions. This involves creating internal strategies, identifying high-emission suppliers, and offering support through incentives, penalties, or knowledge-sharing. Data-driven tracking will help refine approaches and ensure consistent progress.

Looking ahead

The refrigeration industry is facing a decisive decade. Retailers and their technology partners must navigate not only regulatory deadlines but also a rapidly shifting economic and reputational landscape. Those who act decisively will cut costs, reduce risk, and build climate credibility. Those who stall risk spiralling costs and unnecessary emissions.

The technology is here. The economics add up. The pressure is mounting. For the refrigeration sector, the path to net zero is not just about compliance – it’s about securing long-term resilience in a warming world.

About EIA:

The Environmental Investigation Agency’s climate team campaign works to avert climate catastrophe by investigating the criminal trade in refrigerant gases, strengthening and enforcing regional and international agreements that tackle fossil fuels and climate super-pollutants, including ozone-depleting substances, hydrofluorocarbons and methane, and advocating corporate and policy measures to promote sustainable cooling. Detailed information on F-Gas-free cooling technologies can be accessed via its Cool Technologies platform: www.cooltechnologies.org